Typically when I travel, if I'm able to splurge on a nice hotel, I will pick a smaller boutique hotel, preferably one that is historic. The St. Francis in San Francisco, built in 1904, is a bit large for my tastes, but it is still a well-maintained facility that pays homage to its history and classic sense of style.

The expansive lobby gives an impressive "welcome" to guests as they walk in.

The hotel is distinctive for its historic Magneta Grandfather Clock, located in the lobby. It was the first master clock (controlling all the other clocks in the hotel) brought to the west and has served as a meeting place for San Franciscans since 1907, inspiring the phrase "Meet me under the clock!"

This vintage photo showing Shirley Temple at the St. Francis hangs near the lobby.

Plenty of cool light fixtures (both indoor and outdoor) for me to obsess over:

EVERY classic hotel has a shoeshine stand; the St. Francis is no exception.

This hallway leads to room 1221, one of the most infamous rooms in the hotel.

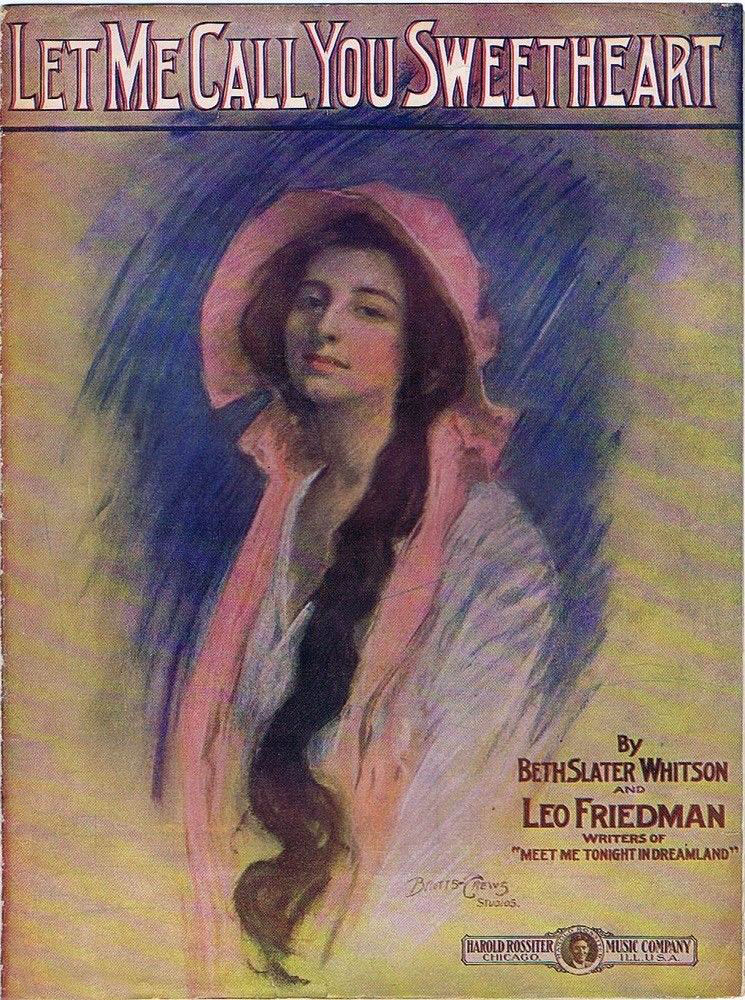

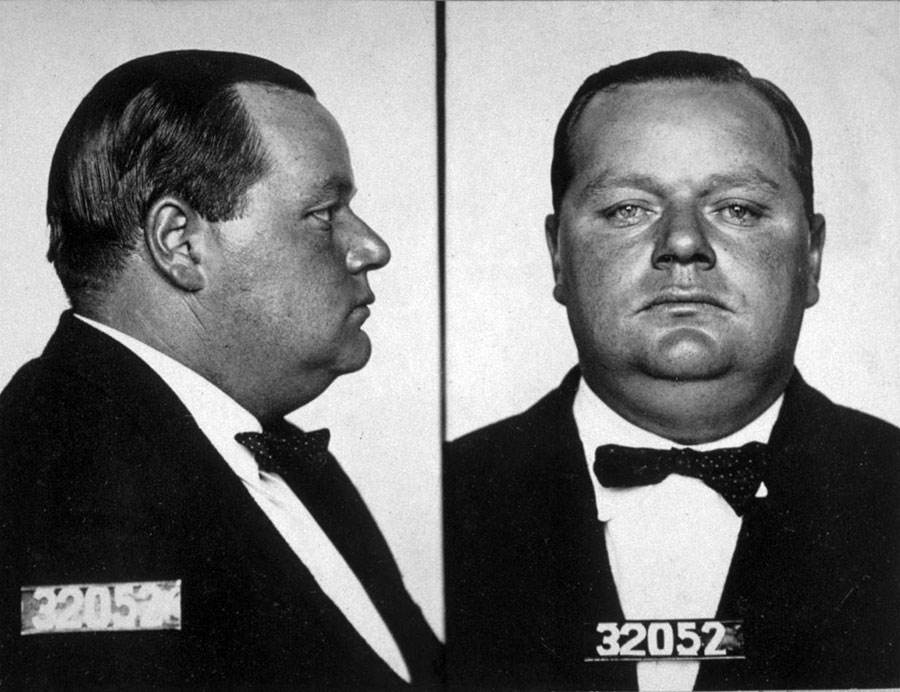

On September 5, 1921, silent screen comedian Fatty Arbuckle held a Labor Day party in suites 1219, 1220, and 1221, with friends and acquaintances from Hollywood. One guest was a young actress from Hollywood named Virginia Rappe, 26, a model and bit-part actress, whose greatest claim to fame was that her portrait graced the cover of the sheet music for “Let Me Call You Sweetheart.”

Virginia Rappe already suffered from chronic cystitis, a condition that flared up whenever she drank (which was often). She developed a reputation for getting drunk at parties and tearing at her clothes from the resulting physical pain. She had also undergone several poorly-done abortions and was preparing to undergo another as a result of being impregnated by her boyfriend, director Henry Lehrman.

In mid-afternoon Arbuckle summoned a house doctor and reported that Rappe was sick. She was taken to another room and put to bed, with Arbuckle returning to Hollywood the next day.

A few days later Arbuckle learned that Rappe had been taken to the hospital and had died, and that her friend Maude Delmont, who had been at the party, told police that Arbuckle had assaulted and raped her. Delmont's testimony was later regarded as unreliable by the police when it was discovered that she had a lengthy prior record of extortion. There was also a telegram she had sent to friends that read, “We have Roscoe Arbuckle in a hole here. Chance to make some money out of him.” The doctor who examined Rappe found no evidence of rape, either. Regardless of the facts, the story blazed across the country with scandalous newspaper headlines.

Arbuckle was brought to trial for manslaughter in November 1921. Arbuckle's lawyers argued in two trials that Virginia Rappe had died of natural causes, caused by too much alcohol; both trials ended with hung juries. Arbuckle was finally found not guilty in the third trial that ended on April 12, 1922, when a jury decided (in five minutes) that Arbuckle was not guilty. “Acquittal is not enough for Roscoe Arbuckle. We feel that a great injustice has been done to him... there was not the slightest proof adduced to connect him in any way with the commission of a crime. He was manly throughout the case and told a straightforward story which we all believe. We wish him success and hope that the American people will take the judgement of fourteen men and women that Roscoe Arbuckle is entirely innocent and free from all blame,” the jury foreman told the court.

Arbuckle was free, but his career was ruined. His films were withdrawn by Will H. Hays, the President of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America. To escape being blacklisted, Arbuckle directed a few films under an assumed name, William Goodrich. In 1932 Arbuckle signed a contract with Warner Bros. to star under his own name in a series of two-reel comedies. These six shorts are the only recordings of his voice. The films were very successful in America and led to him signing a contract on June 29, 1933 at Warner Bros. to make a feature-length film. He supposedly said, "This is the best day of my life." Sadly, he suffered a heart attack later that night and died in his sleep at the age of 46.

Entertainer Al Jolson ("The Jazz Singer") collapsed and died of a massive heart attack while playing poker in his St. Francis suite (the same one from the Arbuckle scandal) on October 23, 1950; he had just returned from entertaining the troops in Korea. This photo was taken September 17, 1950:

From the New York Times:

Al Jolson, “The Jazz Singer,” died at the St. Francis Hotel here tonight. He had recently returned from Korea after entertaining troops there.

Death came just after 10:30 P.M. (PST) as Mr. Jolson was playing cards in his room with friends. He was in San Francisco to be the guest star on the Bing Crosby radio program scheduled to be recorded Tuesday night.

Mr. Jolson checked in at the St. Francis today. He was playing gin rummy with Martin Fried, his arranger and accompanist, and Harry Akst, songwriter and long-time friend.

His last words were said to be "Boys, I'm going." The Al Jolson Society held a séance in the suite, but there were no signs of Jolson. Still, there are staff members who insist that Jolson, Arbuckle, and Barrymore haunt Suite 1221.

There are a number of displays throughout the hotel filled with memorabilia documenting the hotel's history:

The rooms are large, but seem a bit lacking in warmth and personality.

Still, you can't beat the location and service...and the history.

See more Westin St. Francis Hotel photos on my St. Francis Hotel web page.

2 comments:

Have you been to the Palace Hotel in San Francisco? Now that's a hotel!

Palace is right! Wow! Can't believe I've never noticed that hotel before.

Post a Comment