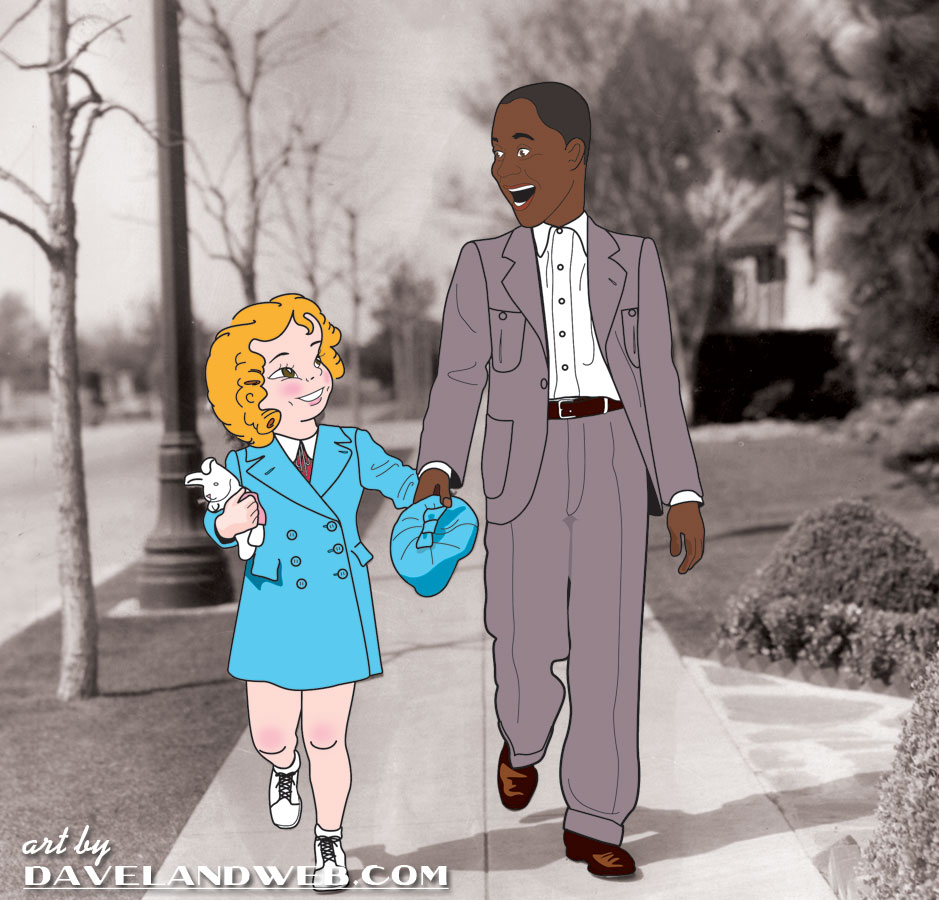

Shirley Temple and Bill Robinson; a duo that made Hollywood history as the first interracial dance team. Their first onscreen pairing was in the 1935 movie “The Little Colonel.” Shirley recalled her first meeting with Robinson in her autobiography Child Star:

“Can I call you Uncle Billy?” I asked. “Why, sure you can,” he replied. After a few steps he again stopped. “Mr. Robinson doesn’t fit anyway.” He grinned broadly. “But then I get to call you darlin”.” It was a deal. From then on whenever we walked together it was hand in hand, and I was always his “darlin’.” At first we practiced in the regular mirrored rehearsal hall. Then we found it more convenient to use a contraption that when folded looked like a wooden box, but when unfolded, became three steps, up on side and down the other. At any spare moment, anywhere, we could practice.

“We’ll have a hand-squeeze system,” he proposed. “When I give you three quick squeezes, means we’re coming to a hard part. One long squeeze, really good, darlin’! No squeeze at all? Well, let’s do it again.” Before long his system of signals became superfluous. “Now we just let those hands hang loose,” he instructed. “Limp wrists, loose in the shoulders. There, that’s it! Copacetic! Now let’s get your feet attached to your ears.”…Fondest memories of dancing with Uncle Billy come not only from our camera takes but from rehearsals, up and down that portable stile, or in any convenient corner. Practicing until each move became unthinking was a joy. Learning, an exhilaration. In devising some nuance of movement or sound to make the dance only ours lay the ultimate satisfaction. Once we had reached the point of “roll ’em,” each of our routines had been perfected, ready for only a final moment of elation in a long sequence totally devoid of drudgery.

Flash forward to 1944, Shirley later recalled their last public performance:

Fifty thousand people collected in the mall of Central Park to celebrate the annual New York Mirror Sports Festival. Uncle Billy Robinson and I met onstage, our first encounter since “Little Miss Broadway” five years earlier. Appearing almost unchanged, he held my hands and suggested we perform a dance for old times. His two-toned shoes flickered with the same old magic I remembered so well, but I found myself laboring to follow his lead. Dancing the shim-sham-shimmy in high heels is not easy. “Haven’t done this since I was seven,” I told him after we had finished. “Excuse me if I wasn’t so hot.” “Darlin’,” he replied with that familiar slanted smile, “you were A, which means really sensAtional.” “Do I get a chance to visit you and Fannie[Robinson’s wife]?” I asked. A solemn little cloud passed over his face…[he] sighed, and waggled his head sideways.…Many times he and Fannie had been guests in our home, yet not once had I seen where they lived in Los Angeles. Wiser by far about racism since my first awareness acquired at the Desert Inn, I still believed that professional comradeship formed an automatic bridge across a chasm dug between people in the name of racial prejudice. A second chance to get my answer occurred at the Harvest Moon Ball in Madison Square Garden.…Leaving the central platform, we held hands as we always had, and at the top of the aisle I again asked when I could visit.…his face suddenly tinged with a calm, gentle expression. “No way, darlin’.” He gave my hand a reassuring squeeze. “Just no way.”

The two had one final visit at the end of 1949, just as Shirley was in the midst of divorce proceedings.

My cherished dance partner Bill “Bojangles” Robinson came to Los Angeles for a one-night charity performance. Dismissing the significance of my impending decree, he disclosed that he and Fannie had separated some time before, and that he was now happily remarried and had a ten-year-old adopted daughter. “But she can’t dance,” he said, cocking his head sideways and flashing that same wide-eyed, toothy smile so indelibly imprinted in childhood memory. “I’m in hard times now, and gray too.” He ruffled on hand over his hair. “But after all, I’m seventy-one.” For a while we sat together, contentedly recalling the happy past we had shared. “Both of us come a long way since that first staircase dance way back in 1934.” He gave a delighted, rolling chuckle. “Still plenty to laugh about.” Within several days, on Thanksgiving, Uncle Billy lay dead.…30,000 people lined New York City streets as his funeral cortege wound through Harlem, led by a brass band of trumpets, tubas, and trombones, stepping slowly in lockstep. What they played was not a dirge, however, but music Uncle Billy would have wanted, dance music in slow motion. Our entertainment careers were ending just as our duets always had, in good time and in step.

What made Robinson so special to Shirley? She later recounted the reason to NPR:

Bill Robinson treated me as an equal, which was very important to me. He didn't talk down to me, like to a little girl. And I liked people like that. And Bill Robinson was the best of all.

See more Shirley Temple photos at my main website.

2 comments:

Wow, that's a great story about Bill and Shirley. What a shame that she couldn't get invited over but I see why now. It's always so sad to see these huge entertainers having financial trouble later in life but at least they made millions of people happy and had huge turnouts at their funerals. Robinson sounds like a genuinely nice guy at a time when people weren't so genuinely nice to him.

Excellent glimpse of the past. Well done Dave! KS

Post a Comment