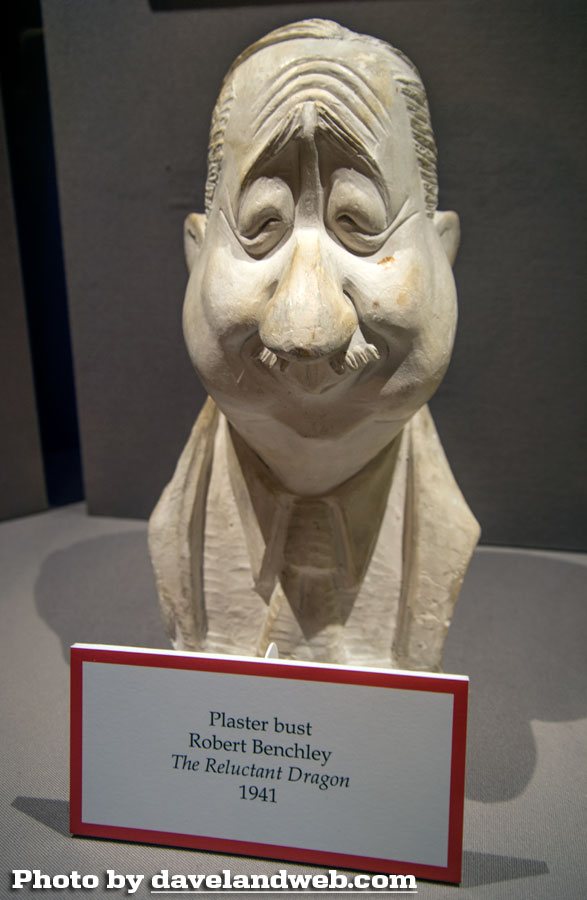

The names Shirley Temple and Robert Benchley don’t really go together in the grand scheme of things, but they intersected (professionally) at least twice. The American humorist is probably best known for his pieces in Vanity Fair and the The New Yorker, his membership in the Algonquin Club (see previous post), and some memorable Hollywood supporting roles. Disney’s “The Reluctant Dragon” (1941):

and Hitchcock’s “Foreign Correspondent” (1940). Shirley and Robert were “together” in the April 1939 issue of True Confessions magazine. That sounds so lurid! Shirley had a beautiful two-color full page photo promoting “The Little Princess”:

Meanwhile, Benchley got a cigarette ad in black and white:

This is not surprising, as 1939 was considered the humorist’s worst year careerwise: both his radio show and MGM film contract were canceled and The New Yorker replaced him with Wolcott Gibbs, because his Hollywood exploits prevented him from spending enough time on his writing gigs.

Benchley supported a teenage Shirley in 1945’s “Kiss and Tell” for Columbia Pictures. He played Corliss Archer’s (Shirley) Uncle George. In her autobiography, Child Star, Shirley gives Benchley a brief mention associated with a very sad event:

Humorist Robert Benchley, author-cohort from “Kiss and Tell,” honored us [then husband John Agar] at a candelit dinner party at his San Fernando Valley home. Jack was dancing with a starlet type, a bit player from a recent low-budget movie. Lithe and range with cascades of blond hair and widely flared, sensuous nostrils, she had already made biting remarks about my compact stature.…Driving home to our honeymoon cottage, Jack was merciless. “Always wanted to marry a long-legged model,” he said. “Not someone like you.” Already stunned, I could hardly believe my ears. But playing second fiddle was against my nature. “Trouble with people who have those nineteen-inch waists,” I replied, “their other measurements are small too. Including the head.”

Don’t mess with Shirley, who was perfectly capable of writing her own quips!

“Kiss and Tell” was released on October 18, 1945, Benchley was dead within a month from a cerebral hemorrhage at age 56. From the Algonquin Rondtable website:

Throughout World War II Benchley kept up an extremely busy pace in Hollywood. He lived in a bungalow in the Garden of Allah and worked steadily in movies and radio. In his early fifties Benchley eventually suffered from health problems exaggerated by his heavy drinking. He was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver and high blood pressure. In late 1945 he returned to New York for a break, but his health slid downhill. He collapsed in his room at the Royalton Hotel on West Forty-fourth Street. He died in the Harkness Pavilion at the Columbia University Medical center on Fort Washington Avenue, on November 21, 1945. Benchley was a teetotaller until he fell in with the Vicious Circle in the Speakeasy Era in his thirties. Twenty years later, drink did him in.

Here he is with Charles Butterworth at the Garden of Allah, both looking a little less than sober.

See more Shirley Temple “Kiss and Tell” photos at my main website.

4 comments:

Imagine being married to Shirley frickin' Temple and somehow it's not enough for you. I mean, I have yet to observe a single John Agar movie block on the TCM schedule, but okay. >D

I hear ya; on the plus side, the two had a beautiful daughter together.

LOL, the "John Agar Film Festival." Not happening.

Warner Archive released Benchley's MGM theatrical shorts as a set. After MGM he did a similar series at Paramount, then returned to MGM for a handful more before his death.

In some he's basically an actor, playing slightly put-upon Babbits trying to bluff while looking increasingly silly. These are mildly amusing. The better ones have him as a smug authority lecturing the camera, sounding like one of his more whimsical written pieces, such as "The Courtship of the Newt"; or as a hapless speaker before a club or some other in-film audience, such as "The Treasurer's Report".

Son Nathaniel and grandson Peter both wrote successful novels, one of the few forms Robert didn't conquer.

Post a Comment