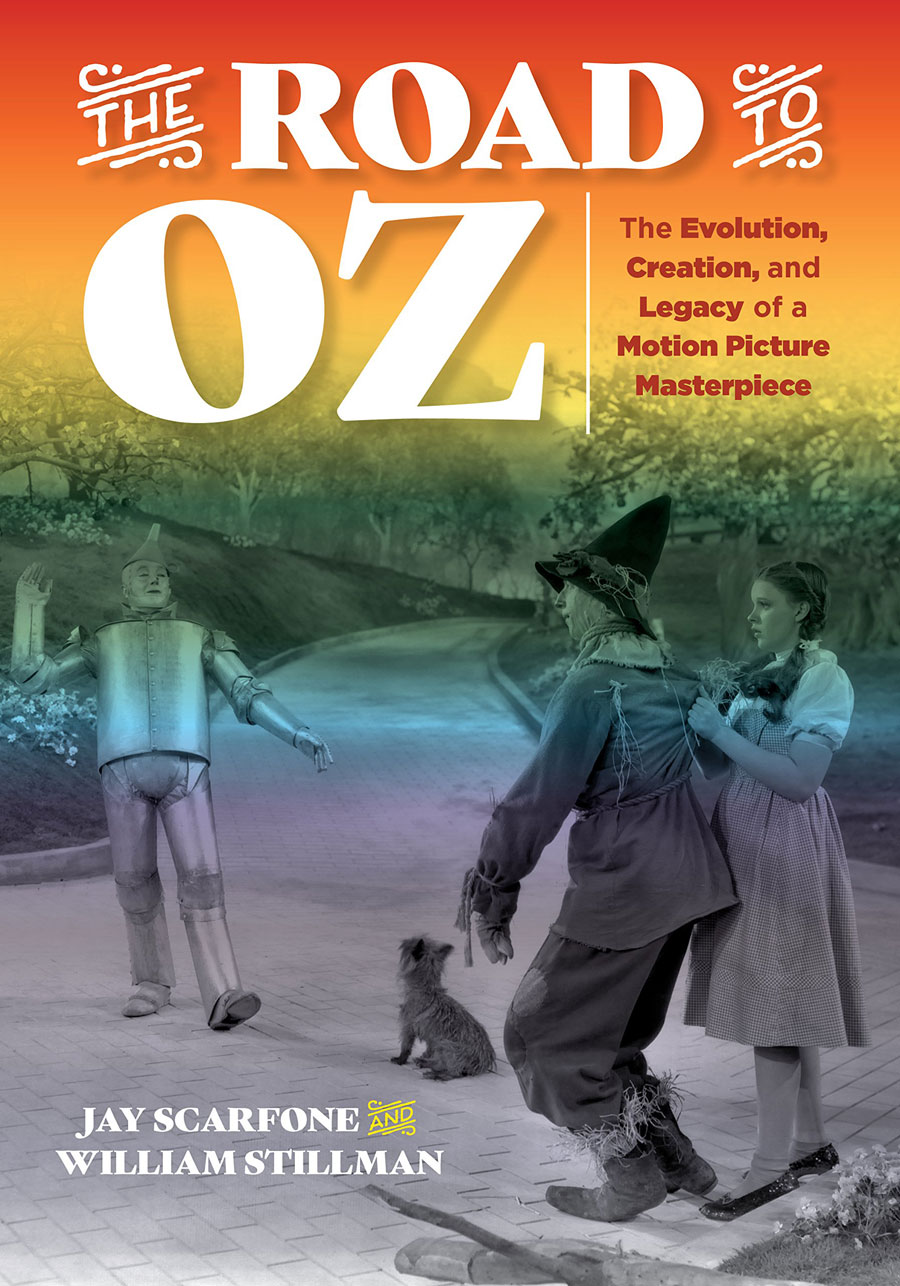

Have you seen the most recent book on the 1939 movie “The Wizard of Oz”? Just when you think nothing else new could be uncovered, authors William Stillman and Jay Scarfone publish “The Road to Oz: The Evolution, Creation, and Legacy of a Motion Picture Masterpiece.” Organized into three sections (Evolution, Creation, and Legacy), this new illustrated volume is a detailed account of how one of my very favorite movies came to be.

Did you know that there was a wildly successful “Wizard of Oz” stage version that took over Broadway’s Majestic Theatre from January 1903 to December 1904 and ran for 293 performances? Very few today do, but at the time, David Montgomery and Fred Stone who played the leads of the Tinman and the Scarecrow were the toast of Broadway. Just one of the many nuggets you’ll discover in “The Road to Oz.”

Author William Stallman graciously granted my request for an interview, the first part of which deals with what is covered in (of course) part one of the book, Evolution.

1. Who actually wrote the musical play? Was L. Frank Baum involved very much? If so, why was the plot so convoluted and why did it deviate so far from the original book?

A: Baum and composer Paul Tietjens at first crafted a script that adhered to the plot of the original book but when director Julian Mitchell was assigned to the project, he was dissatisfied and, with gag writer Glenn MacDonough, revised the script adding its spectacle, romance, topical humor of the day, and making the comedic duo of the Scarecrow and Tin Man the show’s focal point. The alterations worked, and the show was a smash hit.

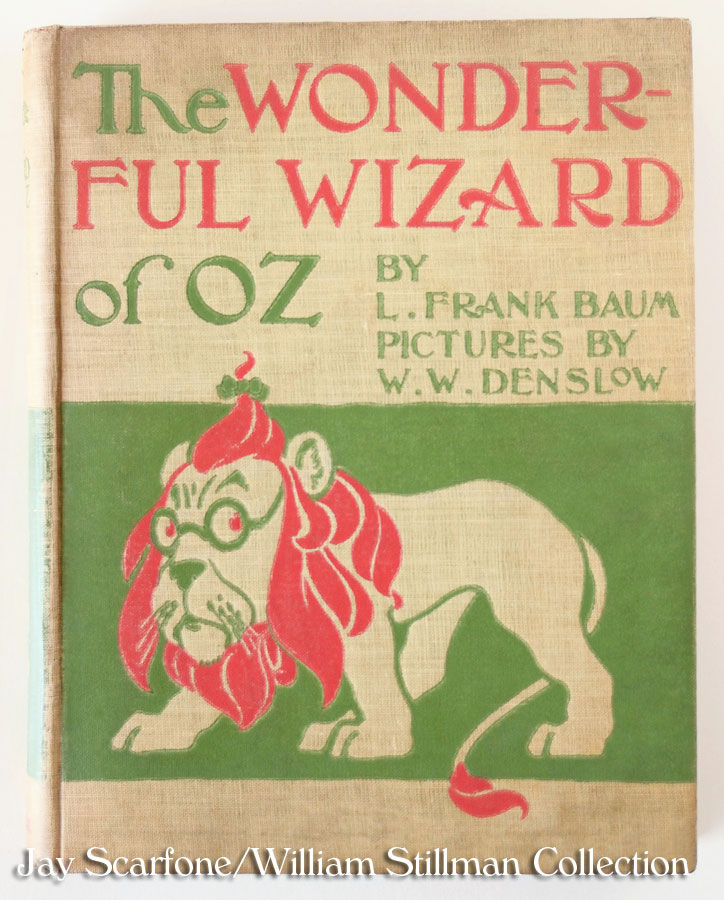

A first edition of Baum’s original story:

2. Have there been any attempts to revive it since?

A: There have been no serious efforts to revive it on so grand a scale as a Broadway production, but there have been a few isolated instances of it being performed, most recently in 2010. It has, however, long since been overshadowed by the sentimental familiarity of the 1939 MGM film and the show’s humor is now long outdated.

Fred Stone and David Montgomery as the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman from the original stage version:

3. I seem to remember that one of the songs from the play was used as background music in the 1939 movie (if I remember correctly it was during the talking apple scene); is that true, and if so, did they have to get permission or pay any kind of royalty?

A: Herbert Stothart, MGM’s musical maestro, sampled a variety of other composer’s works (as you’ll read in great detail in “The Road to Oz”). No songs from the 1902 show were used, and the underscoring in the apple orchard sequence is a 1905 song titled, appropriately enough, “In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree.” It may be heard here:

Another shot of Fred Stone and David Montgomery as the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman from the original stage version:

4. Any other connections between the stage play and the 1939 movie you'd care to discuss would be great.

A: Trivia that may interest longtime admirers of the Judy Garland film is that, in the show, Dorothy is accompanied to Oz by her pet calf Imogene instead of her dog Toto; the Cowardly Lion is also performed by a man in a suit but the character is minor and remains mute throughout except for a couple roars; and, most significantly, there is no Wicked Witch of the West. The show’s best remembered scenes were the Kansas cyclone and the transformation of the poisonous poppy field into a wintery tableau—something that was retained in the MGM film.

5. I also read in your book that Maud Baum thought Walt Disney was dishonest. Do you have any more info on this? Based on the relationship he had with PL Travers, the author of “Mary Poppins,” this seems like it could be a similar situation? I know Mrs. Travers was vehement that she did not want to work with Disney again and that she thought he had hoodwinked her.

A: After meeting with Roy Disney, Maud decided that the Disneys were untrustworthy and seemingly wanted to buy up the remaining Oz book film rights (after MGM acquired “The Wizard of Oz”) merely to corner the market with no guarantee that any film project would be scheduled as forthcoming. Instead, she entered into a contractual arrangement with Kenneth McLellan, an animator who had worked for Disney previously. McLellan impressed Maud with his passionate drive and showed her a sample proposal for his Oz cartoons as well as merchandising plans for Oz character dolls. Her agreement with McLellan was still in full effect at the time of MGM’s Oz (cartoons were considered a separate medium from live-action motion pictures) but, ultimately, McLellan was unable to secure financial backing needed to fund his animations. Ruth Plumly Thompson, who continued the Oz book series after Baum’s 1919 death, was greatly exasperated when Maud Baum dismissed the Disneys as Thompson held hopes for the global marketing of her own Oz stories.

Here, Judy Garland visits with Maud, Baum’s widow:

6. While I 100% believe Judy Garland was the best choice to play Dorothy in the 1939 movie, I am fascinated by the mythology that has grown around the story of Jean Harlow, Clark Gable, and Shirley Temple. Based on all the researched information I have read, that does seem like a total myth. Any idea how that rumor was started?

A: It does appear as though there is some truth to the rumor, but the timing has been conflated over the years. It would seem as though there was a brief window of time when such an arrangement was all plausible in spring 1937, but that would have been for a different film version of “The Wizard of Oz” and not the version that became the Judy Garland picture. We lay out the logic for this in our narrative, cobbled together from information gleaned in our research. Shirley Temple herself, who had a near-photographic recall of her childhood, even wrote with clarity about it in “Child Star,” her autobiography.

7. I am also fascinated by Roger Edens' visit to Fox to hear Shirley sing. Did Temple actually perform just for him or did he just observe her filming one of her movies?

A: Regrettably, we have no further information about what was a very minor concession at the time to placate Nicholas Schenck, president of Loew’s Inc., MGM’s parent company; Schenck was pressing for Temple as the lead to ensure audience turnout and justify the $3 million budget for Oz. Reportedly Temple did sing for Edens and he determined that she lacked the vocal bravura for Dorothy as MGM was envisioning the role.

Here, Shirley Temple with Gale Sondergaard (the original choice to play the Wicked Witch in Oz) in 1940’s “The Blue Bird”:

8. It was interesting to see "The Blue Bird" listed in the Top 20 Unfilmed Classics by Film Daily in 1937 based on a nationwide poll of fifteen hundred newspaper critics, editors, and columnists; definitely shows why Darryl Zanuck invested so much into that for Shirley. Did Zanuck actually make an offer to Goldwyn for Oz, and if so, how far away from Mayer's $75,000 was it?

A: No known record survives to indicate what Zanuck’s offer was although it was reported in the press that he had bid on the property for Shirley Temple. Even if Zanuck’s bid matched that of MGM, Goldwyn would’ve deferred to MGM and not Fox as Goldwyn had a strong personal and professional history with Mervyn LeRoy, for whom the book was purchased.

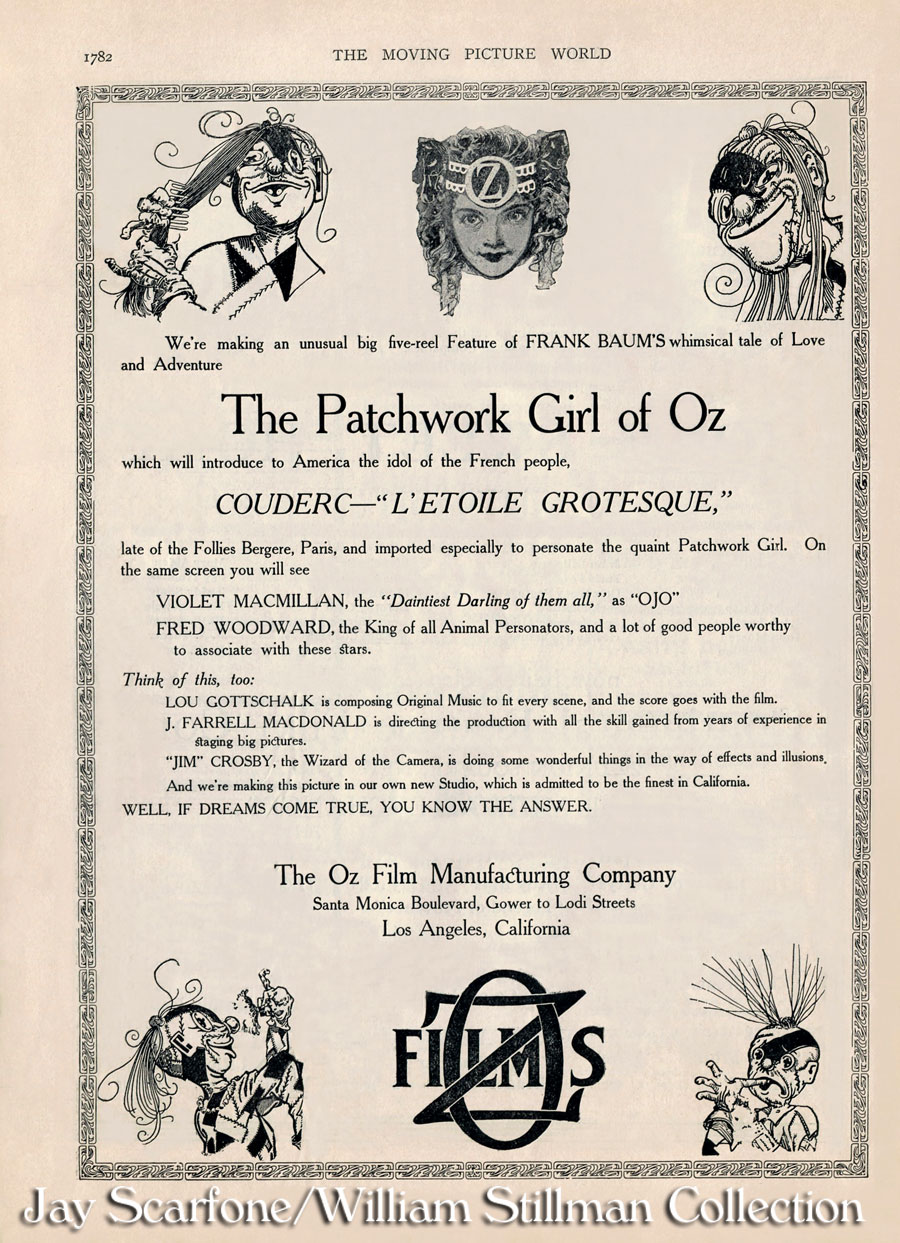

9. Of all the Oz movies that Frank Baum actually made, how many of these still exist? And if they do exist, can the public see them/purchase them?

A: “The Patchwork Girl of Oz” and “His Majesty, the Scarecrow of Oz” (both 1914), silent films created by Baum’s Oz Film Manufacturing Company, are extant and are available to view on YouTube as is a 1910 silent version of The Wizard of Oz, produced by Selig-Polyscope and with which Baum had no direct association. They are quaint and all rather cutting edge for their time period in terms of unusual optical effects. The films may be viewed at the following links:

Stay tuned for more installments! Many thanks to William Stillman for today’s blog post!

See more 1939 “Wizard of Oz” photos at my main website.

very cool. been in possession of a few oz books of theirs for decades. X

ReplyDeleteover 30 years ago (!!! time does fly!!!) I saw a nitrate print of a silent Wizard film at the Eastman House in Rochester, NY - but I think it was the 1925 version with a small role played by Oliver Hardy.

ReplyDelete